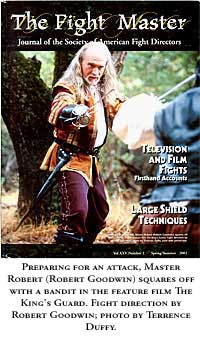

Making a Swashbuckler Movie

The King's Guard

—by Robert Goodwin (as published in "The Fight Master" - Journal of the Society of American Fight Directors - Spring/Summer 2002. All photos on this page as published in this issue of "The Fight Master" are by Terrence Duffy.)

T

he King's Guard was the first sword movie shot in the U.S. since Robin Hood: Men in Tights. Most of the movies one sees with swords in them are filmed abroad. The producers can make more money by not paying union wages or residuals, except to principal actors. Thus all the run-away productions with sword work in them are shot in other parts of the world.

To work on a film project from the beginning is a labor of love. One will never work harder for less, be frustrated more, and have one’s heart broken as much as watching a project go through tis growing pains. The other edge to this sword is the pride of having helped complete the impossible. The miracle was making a period film, for under one million dollars, after its conception only one year earlier. Most projects in Hollywood take anywhere from two to ten years. Part of this minor miracle was being able to work with friends and students. This gave the project an energy that would be difficult to duplicate. Usually films are made by a group of strangers acting together.

The Idea

Jonathan Tydor got the idea for the screenplay after watching sword classes being taught at Film Fighting LA at the Westside Fencing Studio in Culver City. From a class of twelve, Tydor chose to focus on four FFLA members. He began writing the script with this author as Master Robert, Malcolm Earl Robinson as Donald, Casie Fox as Katie, and Abba Elfman as Adam. Through discussion it was decided to set the action in the middle of the seventeenth century because it was a period when rapier and dagger were in transition. Assuming the script was in the works, FFLA began gearing up for the possibility of working on such a vital and challenging project.

Tydor's novel idea was that if FFLA members were willing to put up the fights while he raised money and wrote the script he would be able to offer any prospective producers considerable savings in time and money. Prospective backers did not always know what the period was until Tydor showed the photographs of the four FFLA members giving a demonstration in costume.

Rehearsals and Training

Training began with actor/combatants for the various roles and fights. Naturally one wants to work with students and others that one has worked with before, because their abilities and work ethics are known. Working on a legitimate project with people one has been teaching and can trust is a rare experience in Hollywood, unless one belongs to one of the stunt organizations that only uses their own people. Then FFLA members were cast, four co-stars and six action actors. Kit Devlin was one of those six action actors and was trained by the Society of American Fight Directors. Devlin was given a line and became eligible for the Screen Actors Guild (SAG).

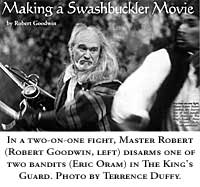

Being SAFD trained, the sword master contacted other SAFD members in the area such as Chris Villa, Payson Burt and Eric Oram. The quality of training from the SAFD is such that one can easily adjust one's skills for film fighting, if needed. The film was shot in the summer of 1999, even though most SAFD members were out of town working, a few were used. One was Eric Oram in the duel of Master Robert against the two bandits.

FFLA was enthusiastic and classes began research in the Italian system of rapier, rapier and dagger, and Spanish fencing as applied to the main gauche. The Spanish techniques were for a sequence that was unfortunately cut the day the scene was supposed to be shot. It was a time of growth for the sword master as well as all others involved. The Italian rapier and dagger had been chosen because of their versatility. This gave the elite guardsmen movements that were visually interesting and could be used in broad or subtle movements. This seemed the natural choice for the king's private guards.

Money and Casting a Low Budget Period Film

Getting start-up money for a new project is difficult. Even though Tydor had established himself as a writer with the feature I Come in Peace, he still had trouble finding the start-up money. What most people do not realize is that without money one cannot get a draw (name actor) for a project and without a draw one cannot get the money. Money will also dictate what co-stars are available. For that reason, and others, the project became SAG. This created some friction in the beginning, not enough money, dealing with agents, and so on. After a few meetings, the director realized that to produce a quality film, SAG sanctioning would be necessary to help attract the appropriate draw. The usual money problems were faced. Due to Tydor's diligence, he located Michael Marcopoulos and Eileen Craft to assume the producers' responsibilities. Before the money was available, the search for the cast, including stunt fighters, had begun.

For those that do not know, working on a movie is demanding enough but being involved in a project from its conception is filled with ups and downs, financially and emotionally. The deal is on, then canceled, then on, then no money. Then a lead signs, then cancels due to a scheduling conflict, and the money pulls out. Then the lead resigns and the money comes back. The business side of film making is so fragile that artists do not want to deal with it. That is why artists have agents, then all the artist has to do is focus on his/her art.

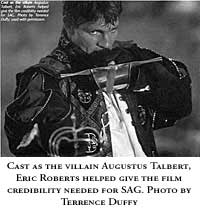

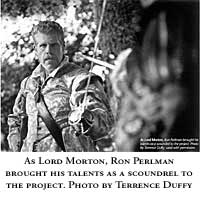

Many times the money fell through and the production was back to ground zero but actors kept on training and rehearsing the fight scenes. Only when Eric Roberts signed on did enough money come in for SAG. The film had its draw. He is a very recognizable villain. Then rumors began about Ron Perlman joining the project. That excited the company even more because his work in the French film, City of Lost Children and other projects were known. Now it felt as if the film was actually going to be made.

The First Real Test of Film Fighting LA (FFLA)

FFLA members auditioned for acting roles, as well as fight roles. Throughout the process some excellent actors and fighters declined working towards the project because of the lack of SAG sanctioning and the time commitment, even though it was explained to them that they would eventually have SAG contracts. At this point class became more about choreography for the scenes in the movie then learning a technique. A lot of personal time was contributed by FFLA members and many others in the collaboration of making this film. The FFLA prepared for the day-to-day grind of a three-week shoot on location.

This would be a test because most of the FFLA members had never been in film or on television. The sword master taught classes Film Fighting technique, adjusting for a one-camera shot: acting the fight, safety, self-defense on the set, working inside the normal/safer fencing measure, adjusting for a hand-held camera, using film language, cueing one's partner to adjust for something/someone they cannot see, fighting in the rain and mud, weapons safety on exiting a corps-a-corps, fighting in a zone, controlling intensity, using the cut in major battles, costuming restrictions and asking everyone to perform a daily aerobic exercise. When it came time to start filming, the FFLA was prepared and eager to begin. Different levels of ability existed, yet everyone contributed as much as they could, with safety always the priority.

Breaking Down the Action Scenes in the Script

The job as a sword master is two-fold: setting the tone of the fights while remaining true to the period and fulfilling the director’s intent. If working with a relatively inexperienced director, one may have to educate as one goes along. After viewing some of the prepared fight scenes, the director expressed his interest in the rough and tumble fighting of the original color Three Musketeers movie while the sword master wanted fights people had never seen before. The sword master wanted the Italian principles of a parry becoming a thrust and a thrust becoming a parry and the linear concepts stressed by Capo Ferro. He wanted to show the techniques used in the middle of the seventeenth century in his duel with the two bandits, Eric Oram and Jon Napier, two excellent swordsman.

The Sarcinian soldiers and bandits' fight was cast out of the production office in San Diego and choreographed by George Ye. To maintain the integrity of the period Ye and the sword master communicated on weapons as well as fighting style. The fencing style of the elite king's guard did not need to be duplicated as the Sarcinians were soldiers, therefore, they fought like soldiers.

Some Notes on Acting for the Camera

Acting for the camera is different from acting on stage. Both are based on the same principles and stage experience is the best foundation one can have, but the demands of a highly charged, emotional day and the shooting out of sequence in film life offers different challenges than one experiences on stage. The actor may be in a battle scene where he is fighting for his life in the morning and be expected to be laughing and enjoying himself at a ball in the afternoon. Then a week later they need a pickup shot from the middle of the battle scene. It is a close up and the actor has to be at the same emotional level he was in the middle of the scene when it was originally shot and still remember the fight choreography. Otherwise they cannot match the shot in the editing bay and the close-up ends up on the cutting room floor. The pick-up shot needed will invariably be the most physically demanding phase of the fight and director and crew will want to film it at the end of a fourteen-hour day. Luckily this did not occur during the filming of The King's Guard.

When an actor is called to the set as a stunt fighter he needs to be in character, focused, physically ready to fight, and bring a safe, emotional level to the scene that is appropriate for the shot. The actor's job is not to outfight, or look better than the principal actor, or in any way make the principal actor look bad or inexperienced, unless directed to do so. One's job is usually to get killed, wounded, knocked-out or run away and allow the principal actor to be the hero. If an actor does not follow directions, he will be asked to leave the set and will be replaced in a phone call by one of the hundreds of stunt fighters available in Hollywood. Plus one cannot ever expect to be called back by that director, producer, casting director or production company. Hollywood has a long memory.

Pacing Yourself

It is too demanding to be the sword master of a film with a lot of fights/duels and also have a high visibility role. When one is not speaking in front of the camera, one's character will be in the background during most of the movie. Plus, when the actor is not in front of the camera he may be training someone, choreographing a new fight scene, or changing an existing one. In the evenings, after a typical ten to twelve-hour day (if shooting in daylight), the actor goes to his room and prepares for the next day's action and his lines. The next morning he is back on the set and the rehearsal time he has with his scene partner, again, will be minimal, if any. Pacing oneself on the set should definitely include eating correctly throughout the day to maintain proper blood sugar level. Sugar should not be eaten to get up for a scene.

Some Final Thoughts

If the actor is cast in a feature film, television movie of the week, or a commercial with sword work in it, he should consider himself very lucky and enjoy it. It will be hard work but the results can be rewarding. The actor should learn self-defense on the set, find the camera and find the light. If the actor cannot see the camera lens, the camera cannot see the actor, and if one is in the shadows, one cannot be seen. The actor may want to stay hidden.

Remember an actor's looks may get him in the door, but he will need the training to do the job well, whether it is acting or acting the fight. One needs to keep training with someone that has skills superior to one's own whenever possible, then when one gets that sword fighting role he can hold his head up and proudly represent his teachers, their teachers, other sword masters and actor/combatants around the world. Remember whenever an actor picks up any sword, he accepts the responsibility of carrying on a tradition founded on honor and respect.